Herodotus on the Egyptian belief of transmigration

123 [...] ἀρχηγετέειν δὲ τῶν

κάτω Αἰγύπτιοι λέγουσι Δήμητρα καὶ Διόνυσον. πρῶτοι δὲ καὶ τόνδε τὸν λόγον

Αἰγύπτιοι εἰσὶ οἱ εἰπόντες, ὡς ἀνθρώπου

ψυχὴ ἀθάνατος

ἐστί, τοῦ σώματος δὲ καταφθίνοντος ἐς ἄλλο ζῷον αἰεὶ γινόμενον ἐσδύεται,

ἐπεὰν δὲ πάντα περιέλθῃ τὰ χερσαῖα καὶ τὰ θαλάσσια καὶ τὰ πετεινά, αὖτις

ἐς ἀνθρώπου σῶμα

γινόμενον ἐσδύνει· τὴν περιήλυσιν

δὲ αὐτῇ γίνεσθαι ἐν τρισχιλίοισι ἔτεσι. τούτῳ

τῷ λόγῳ εἰσὶ οἳ Ἑλλήνων ἐχρήσαντο, οἳ μὲν πρότερον οἳ δὲ ὕστερον, ὡς ἰδίῳ

ἑωυτῶν ἐόντι· τῶν ἐγὼ εἰδὼς τὰ οὐνόματα οὐ γράφω. (from p.141

of

Johann Schweighäuser’s edition; also available at Remacle.org

and

Sacred Texts.com.)

Although I had been thinking of writing an entry on how much the soul weighs according to some of those who have tried to come up with a kind of scientific answer to this crucial question [crucial because it would settle any doubts about the soul’s very existence], I decided to share George Rawlinson’s interesting list of references to the soul gleaned from the works of various authors from the Greco-Roman world after having come across it while trying to find the original text of Herodotus’s History, book 2, section 123.

« [...] les Égyptiens furent les premiers à affirmer que l’âme de l’homme est immortelle. Sans cesse, d’un vivant qui meurt, elle passe dans un autre qui naît, et, quand elle a parcouru tout le monde terrestre, aquatique et aérien, elle revient alors s’introduire en un corps humain. Ce voyage circulaire dure 3.000 ans. C’est là une théorie que, plus ou moins près de nous, plusieurs Grecs se sont appropriés; je sais leurs noms et ne les écris point1.»

1. Hérodote, II, 123

On 26th September 2020, I read the above on page 131 of Maurice Mæterlinck’s Le grand secret (Paris, 1956) after having run a search for the keyword palingenesy (and its French equivalent palingénésie) on my computer. There are many English translations of Herodotus’s History available on the Internet. I stumbled across George Rawlinson’s translation from a link at https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Herodotus/2B*.html#note10.

It reads as follows:

123. [...] The Egyptians maintain that Ceres and Bacchus8 preside in the realms below. They were also the first to broach the opinion, that the soul of man is immortal,9 and that, when the body dies, it enters into the form of an animal1 which is born at the moment, thence passing on from one animal into another, until it has circled through the forms of all the creatures which tenant the earth, the water, and the air, after which it enters again into a human frame, and is born anew. The whole period of the transmigration is (they say) three thousand years. There are Greek writers, some of an earlier, some of a later date,2 who have borrowed this doctrine from the Egyptians, and put it forward as their own. I could mention their names, but I abstain from doing so.

If this is still not clear, transmigration according to Herodotus’s definition of the ancient Egyptian belief is the successive series of migrations it takes a soul over a period of three thousand years to move from the human body and back into it after having being incarnated into the bodies of the various categories of animals based on three of the four elements (i.e., sea/water, land/earth and air – maybe I ought to have written ‘four’ because of the salamander, which is associated with fire).

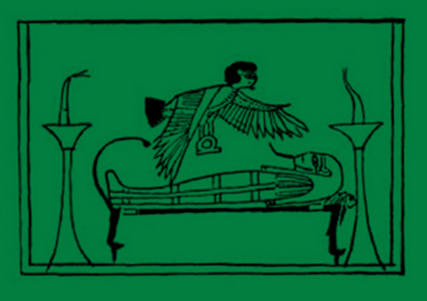

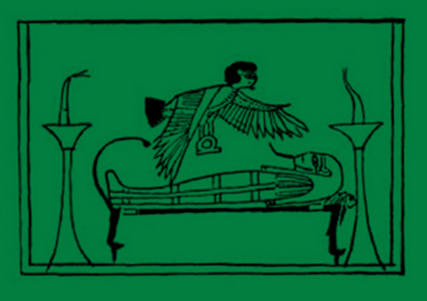

The above is a screenshot from Sir Ernest A. T. Wallis Budge’s Egyptian Magic which I have colourised (the book is in the public domain). It shows ‘[t]he mummy of the deceased lying upon a bier; above is his soul in the form of a human-headed bird, holding shen, the emblem of eternity, in its claws.’ Sir Ernest A. T. Wallis Budge’s description of this vignette was made with reference to the Papyrus of Ani (British Museum No. 10,470, sheet 17 [https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA10470-17]), a papyrus he once owned, and this description was published in his work on the Egyptian Book of the Dead (which can also be downloaded from the Internet Archive https://archive.org/details/TheEgyptianBookOfTheDead/page/n363/).

Below are the notes of George Rawlinson, canon of Canterbury and professor of ancient history at the University of Oxford in the nineteenth century, as published in the American edition of his translation of Herodotus’s History (1862), taken from pages 167 to 169.

8. Answering to Isis and Osiris, who were the principal deities of Amenti. — [G. W.] 9. This was the great doctrine of the Egyptians, and their belief in it is everywhere proclaimed

in the paintings of the tombs. (See At. Eg. W. pl. 88.) But the souls of wicked men alone appear

to have suffered the disgrace of entering the body of an animal, when, “weighed in the balance”

before the tribunal of Osiris, they were pronounced unworthy to enter the abode of the blessed.

The soul was then sent back in the body of a pig (lb. pl. 87), and the communication between

him and the place he has left is shown to be cut off by a figure hewing away the ground with an

axe. Cicero (Tusc. Disp. i. 16) says the immortality of the soul was first taught by Pherecydes of

Syros, the preceptor of Pythagoras, “which was chiefly followed out by his disciple;” but this

could only allude to its introduction into Greece, since it had been the universal belief in Egypt

at least as early as the 3rd and 4th dynasty, more than 1500 years before. Old, too, in Egypt were

the Pythagorean notions that nothing is annihilated; that it only changes its form; and that death

is reproduction into life, typified by the figure of an infant at the extremity of an Egyptian tomb,

beyond the sarcophagus of the dead. (See Ovid. Met. xv. 165, 249, 254, 455.) The same is a tenet

of “the Vedantes of India, and of the Sophis of Persia;” and the destroyer Siva or Mahadeva is also

the god of Generation. (Sir W. Jones, vol. i. p. 256). Cp. Lucret. i. 266:—

1 The doctrine of the Metempsychosis or Metensomatosis was borrowed from Egypt by Pythagoras. (See foregoing and following note.) It was also termed by the Greeks κύκλος ανάγκης, “circle (orbit) of necessity;” and besides the notion of the soul passing through different bodies till it returned again to that of a man, some imagined that after a certain period all events happened again in the same manner as before — an idea described in these lines by Virgil, Eclog. iv. 34:

“Alter erit tum Tiphys, et altera quæ vehat Argo Delectos Heroas, erunt etiam altera bella, Atque iterum ad Trojam magnus mittetur Achilles.”

Pythagoras even pretended to recollect the shield of Euphorbus, whose body his soul had before occupied at the Trojan war. (Hor. i. Od. xxiii. 10; Ovid. Metam. xv. 160, 163; Philost. Vit. Apollon. Tyan. i. 1.) The transmigration of souls is also an ancient belief in India, and the Chinese Budhists represent men entering the bodies of various animals, who in the most grotesque manner endeavour to make their limbs conform to the shape of their new abode. It was even a doctrine of the Pharisees according to Josephus (Bell. Jud. ii. 8, 14); and of the Druids, though these confined the habitation of the soul to human bodies (Cæsar. Comm. B. Gall, vi. 13; Tacit, Ann. xiv. 30; Hist. iv. 54; Diodor. v. 31; Strabo, iv. 197.) Plato says (in Phædro), “no souls will return to their pristine condition till the expiration of 10,000 years, unless they be of such as have philosophised sincerely. These in the period of 1000 years, if they have thrice chosen this mode of life in succession ... shall in the 3000th year fly away to their pristine abode, but other souls being arrived at the end of their first life shall be judged. And of those who are judged, some proceeding to a subterranean place shall there receive the punishments they have deserved; and others being judged favourably shall be elevated to a celestial place .... and in the 1000th year each returning to the election of a second life, shall receive one agreeable to his desire .... Here also the soul shall pass into a beast, and again into a man, if it has first been the soul of a man.” This notion, like that mentioned by Herodotus, appears to have grown out of, rather than to have represented, the exact doctrine of the Egyptians; and there is every indication in the Egyptian sculptures of the souls of good men being admitted at once, after a favourable judgment had been passed on them, into the presence of Osiris, whose mysterious name they were permitted to assume. Men and women were then both called Osiris, who was the abstract idea of “goodness,” and there was no distinction of sex or rank when a soul had obtained that privilege. All the Egyptians were then “equally noble;” but not, as Diodorus (i. 92) seems to suppose, during lifetime; unless it alludes to their being a privileged race compared to foreign people. In their doctrine of transmigration, the Egyptian priests may in later times have converted what was at first a simple speculation into a complicated piece of superstition to suit their own purposes; and one proof of a change is seen in the fact of the name of “Osiris” having in the earliest times only been given to deceased kings; and not to other persons. — [G. W.]

2, Pythagoras is supposed to be included among the later writers. Herodotus, with moreAnd now is your turn to look up information on Herodotus and transmigration:

Enjoy!

PS my entry on Cicero’s claim that souls come from the stars:

http://paulzanotelli.ch/blog/spirituality/soul/souls-are-from-the-stars.html.